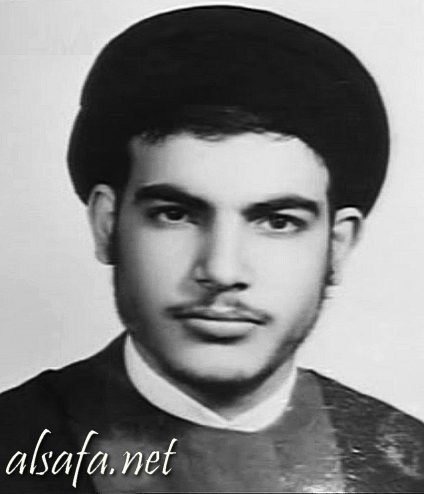

Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah as a young man.

Wow.

Forget the fact that he doesn't lie and he leads an army who has defeated the most powerful countries on earth (the US and Israel). Forget that.

What a darling.

"It is a pity that we have to wait for an Israeli commission to confirm our victory. - Nasrallah, May 2007

The Victory

[48.29] Muhammad is the Apostle of Allah, and those with him are firm of heart against the unbelievers, compassionate among themselves; you will see them bowing down, prostrating themselves, seeking grace from Allah and pleasure; their marks are in their faces because of the effect of prostration; that is their description in the Taurat and their description in the Injeel; like as seed-produce that puts forth its sprout, then strengthens it, so it becomes stout and stands firmly on its stem, delighting the sowers that He may enrage the unbelievers on account of them; Allah has promised those among them who believe and do good, forgiveness and a great reward.

Translation: They are horrendously good looking and cause other people to feel really bad about themselves. Hahaha.

(Sometimes I have to wonder at a movie-going population that idolizes things like "Braveheart" and ignores heroes who are alive and well today.)

http://www.uruknet.de/?p=m32742&hd=&size=1&l=e

March 8, 2007

Aita al-Shaab, Southern Lebanon—Beautiful rolling hills, verdant and fertile, are dotted with olive groves and family tobacco farms in this small village on the border between Lebanon and Israel.

It was here that Hizballah captured the two Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers that kicked off last year’s July-August war. And it was here that some of the fiercest street battles raged as remaining locals joined Hizballah to fight Israeli troops. Most of the buildings still standing are scarred with pockmarks; Aita al-Shaab’s old city is remains mostly flattened, bulldozed by Israeli troops.

As dawn breaks over a ridge separating the 2km distance between Lebanon and Israel, UNIFIL (United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon) outposts glint in the early morning sun. This morning the busy sounds of reconstruction, funded primarily by Qatar, but also by Hizballah (Iran is funding road construction in the region), begins early as migrant Syrian construction workers emerge from the partially destroyed buildings where they’ve encamped.

But in the valleys below the city, rich, red dirt lies fallow even though Aita al-Shaab is an agricultural village. Fields above the town go ungrazed. Since last summer, after Israel dropped about one million cluster bombs in southern Lebanon alone—up to 40 percent of which the United Nations Mine Action Clearing Center (MACC) estimates lie unexploded--most farmers and shepherds have been too afraid to go onto their lands.

Israel has been heavily criticized for dropping 90 percent of the 2-3 million cluster bombs used throughout Lebanon during the last 72 hours of the war, after a cease-fire was agreed upon.

MACC is heading up clearing, but has a long way to go.

Thus far, 60 teams from UNIFIL (UN Interim Force in Lebanon) and private companies have cleared about 10 percent (110,000) of the unexploded munitions. Focus has been on population centers, but fields, forests, and grasslands are much harder to clear. The Israeli government has refused to turn over maps where cluster bombs were dropped, making clearing more time-consuming…and dangerous. Teams are also clearing 400,000 land mines; some are leftovers from previous wars, MACC reports, and some were planted last summer by Israeli troops.

Cluster bomb attacks part of larger plan?

Many I spoke with, like eco-system management and food sovereignty expert Rami Zurayk, believe that the Israeli government’s bombardment is a deliberate attempt to separate people from their lands.

"What’s kept people in southern Lebanon for the past 60 years of neo-liberal policy," he explains, referring to the time period since creation of the State of Israel, "is their profound attachment to the land. I believe it is Israel’s long-term strategy to create the conditions for displacement, just as they have done in Palestine."

Nearby Beint Jbeil, also intensely bombed last summer, is a case in point says Amer Sadadin of Samidoun, a volunteer network that delivered aid to southern villages after the war. Prior to 1948, Beint Jbeil was the region’s largest city with 54,000 residents, he says, but from years of occupation the majority fled elsewhere.

"Beint Jbeil now has only 4,000 people. In the '70s many of these villages were destroyed and people moved to cities like Sour (Tyre). Israel is killing life in the villages," asserts Sadadin.

"The fact that the [Israeli government’s] cleansing operation of South Lebanon is being carried out under the cover of the 'war on terrorism’ allows the international community to turn a blind eye to it," Zurayk maintains.

Comparatively, little reconstruction is taking place in Beint Jbeil; much of the city still lies in a ruin of twisted metal and piles of rubble. The Lebanese government is pushing residents in Beint Jbeil and elsewhere to rebuild with modernized buildings and wider roads, something many local residents refuse.

"The problem is people are being encouraged to bulldoze and build bigger," says Sadadin. "It’s a problem when money comes in with these pre-conditions. Old cities are a maze of history, each stone represents a memory, a relationship to historical continuity. This is exactly what we’re trying to preserve."

Samidoun is now in Aita al-Shaab with volunteer architects who are helping residents rebuild their original homes, while restoring the old city.

Farmers separated from their lands

Aita al-Shaab, as other agricultural villages in southern Lebanon, is suffering huge economic losses from their inability to farm.

Hadjia Habiba has 8,000 square meters of land that have been passed down through generations. Her lands are in parcels scattered on the outskirts of the village. Now in her seventies, Hadjia Habiba has farmed all her life and, like many here, she is economically dependent on her fields.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), agriculture makes up at least 70 percent of the economy in southern Lebanon.

Residents in Aita al-Shaab say their economy is 80-90 percent dependent on agriculture, primarily tobacco and olives.

Some of Hadjia Habiba’s lands are in Kallit Warda, where the Israeli soldiers were taken; the area still guarded by Israeli troops and she hasn’t been allowed there since last summer.

"I didn’t harvest this year at all," she laments. With hundreds of thousands of bomblets littering the fields, no one dared enter and the crops all rotted. Normally, farmers would be planting at this time, instead the fields are quiet.

"We’re still waiting for people to check for cluster bombs, which means I also can’t plant, so there won’t be any harvest this year again either. I live from the tobacco harvest 100 percent. My husband died, so this is how I’ve raised my children."

Shaking her head, Hadjia Habiba says she doesn't know what she is going to do for income.

Millions of dollars in loans have been given to Aita al-Shaab’s tobacco farmers, the only crop the government helps subsidize. About 80 percent of the farmlands here are used for tobacco since it is also the only crop that guarantees an income.

People here expressed anger and frustration with the government for its lack of support. "There’s no compensation from the government for our loss this year!" exclaims Hadjia Sara, another tobacco farmer who worries what will happen when she and others are unable to pay their loans. "Next year, we will have double the payments, plus interest. If we can’t pay, they could take our lands. What is the government doing?"

Farmers estimated only 25-30 percent of Aita al-Shaab’s farmlands are being planted this year, and out of those, only about 25 percent of what is normally planted.

About $280 million from agriculture and fisheries were lost as a result of last summer’s aggressions. Southern Lebanon and southern Beirut, the areas hardest hit by air strikes, are home to the some of the country’s poorest. Its majority are Shi’a.

The FAO plans to set up a farming assistance office in the south, but needs an additional $17 million in order to provide direct aid like replacement of livestock killed.

But, it’s not just economics that have hurt farming communities like this one, the social fabric has also been damaged. "Everyone helps to harvest each other’s lands, take the tobacco to the drying rooms, and then harvest the next field, " says Hadjia Zahra. "It was a collective effort, part of our village life. Now, we sit in our homes and don’t go out. Only half the people have returned. We are still in a state of mourning."

Of the 800-900 homes destroyed, about half have been rebuilt. The 7,000 or so people who’ve returned are crowded together, living with their families until their homes are completed.

The killing continues

Meanwhile, since the bombing stopped last August, some 200 people have been injured and another 30 killed from cluster bombs. Many referred to them as "anti-children" mines because their bright colors attract youngsters, who don’t understand their danger.

In September, three children from Aita al-Shaab were severely injured when a cluster bomb went off. Um Hassan's son was one of them.

"Two of the little village girls had gone back to their home and they found a dead fighter inside, still covered in blood," says Um Hassan. "Cluster bombs had been planted around his body as a booby trap. Thinking they were toys, the girls picked one up and went into the street to play. My son saw them and recognized the bomb from the [educational] posters. When he told them to throw it away, they panicked and threw it at his feet where it exploded."

All the children were badly injured, but Um Hassan’s son was the worst. Just 10 years old, his abdomen was completely ripped open, his intestines spilling out. He spent the next several months undergoing four operations. Hassan is finally back to attending school, says Um Hassan, but his condition is still fragile; remaining shrapnel in his stomach makes her son vulnerable to infection.

Another woman spoke of a nearby villager who was killed when harvesting his olives. "He pulled on the branches and a cluster bomb fell on his head," she says sadly.

Fortunately, these have been the only accidents here, but they are reminders of the dangers that await farmers and their children on uncleared lands.

While the MACC forces are working hard to remove remaining cluster bombs, they say farmlands and forested areas are the most difficult to clear. Bomblets hide in tall grasses and in branches of trees and wash down hills after rains to re-contaminate areas already cleared.

"This has a big psychological effect," says Sadadin. "Some friends and I went for walk when the spring flowers came, but there was a constant fear inside."

"Children here are thinking about the war more than the classroom," said another villager. "Israel wants peace, but they want us to pay for it."

Resistance takes many forms

Yet, despite the constant fears of unexploded ordnance and another Israeli attack, residents are resolute about staying in Aita al-Shaab.

Aita –al-Shaab is infamous for holding off Israeli forces last summer during three separate attacks, and people are proud of this fact. They say their resolve is even firmer than before. But for the people here, resistance is far more than just fighting.

Having watched other villages evacuated over the decades, residents say they will not abandon Aita al-Shaab.

"They tried to destroy us," exclaims Hadjia Zahra, of the Israeli forces, "but we’re not leaving! Some of us came back when the Israelis were still here. This war, people ran away, next time we’ll stay!"

When I asked one olive farmer if she is scared to harvest, she shakes her head determinedly and says no. "I’ve learned how to identify them, so I’m not afraid. And if I’m killed, then I will just join the martyrs already in heaven," she says, referring to those who died defending the village. Defying her fears of the cluster bombs is this woman’s form of resistance.

"The memory of occupation is strong here," says Sadadin. "Weapons are one tool, but resistance is also something social. Just staying on your land is a form of resistance and people here understand that."

No comments:

Post a Comment